What Is Foreclosure?

Quick Answer

Foreclosure is when your home is seized when you fail to repay your mortgage. It can upend your life and cause serious damage to your credit.

Foreclosure is when a lender takes possession of a home because a borrower fails to repay their mortgage. It's a harrowing experience for any homeowner, and it has serious consequences for your credit.

Foreclosure is a tightly regulated process that requires multiple notices to the borrower and, often, a judge's review before proceeding. The steps in the foreclosure process and the timeline for their completion can vary by jurisdiction as well as the lender's policies and the housing market where the home in question is located.

What Is Foreclosure?

Foreclosure is a legal process where the lender takes ownership of your house after you default on your mortgage payments. The foreclosure process differs depending on where you live.

To understand foreclosure, it's helpful to review how a mortgage works. A mortgage is a type of secured loan that uses the financed property as collateral. As with other secured loans, mortgage contracts allow the lender to seize the collateral—in this case, the home—if payments aren't maintained. The lender then typically resells the home in an effort to recoup as much of the outstanding loan amount as possible.

Types of Foreclosure

U.S. law defines three types of foreclosure procedures. Which ones could apply to you depend on where you live and the specific terms of your mortgage contract.

Judicial Foreclosure

In a judicial foreclosure, the lender files suit to begin the process, typically after the borrower misses three consecutive mortgage payments. A letter notifies the borrower that foreclosure will begin if they don't get current on the loan within a specific time limit—often 30 days. If payment is not made in time, the property is seized and sold at public auction. All states allow judicial foreclosures, and some require it.

Power of Sale (Nonjudicial) Foreclosure

In 29 states and Washington, D.C., mortgage contracts can include a "power of sale" clause. If your mortgage contains this language, the lender can auction a foreclosed property without involving a judge. The lender is required to issue notices to the borrower and observe a waiting period that varies in length by jurisdiction before proceeding. In some states the borrower can file suit to have a judge review the process, so they're considered both judicial and nonjudical foreclosure states.

| Judicial foreclosure states | Connecticut, Delaware, District of Columbia, Florida, Hawaii, Illinois, Indiana, Iowa, Kansas, Kentucky, Louisiana, Maine, New Jersey, New Mexico, New York, North Dakota, Ohio, Oklahoma, Pennsylvania, South Carolina, Vermont and Wisconsin |

|---|---|

| Nonjudicial foreclosure states | Alabama, Alaska, Arizona, Arkansas, California, Colorado, Georgia, Hawaii, Idaho, Maryland, Massachusetts, Michigan, Minnesota, Mississippi, Missouri, Montana, Nebraska, Nevada, New Hampshire, North Carolina, Oregon, Rhode Island, South Dakota, Tennessee, Texas, Utah, Washington, West Virginia and Wyoming |

Strict Foreclosure

Connecticut and Vermont permit a form of judicial foreclosure known as strict foreclosure. Under this proceeding, the lender files suit against the borrower who is in default. If the borrower does not pay the mortgage within a time limit specified by the court, title to the property transfers to the lender directly, without a sale. Strict foreclosures generally occur when the amount of outstanding debt exceeds the value of the property.

Learn more: What to Know About the 3 Different Types of Foreclosure

How the Foreclosure Process Works

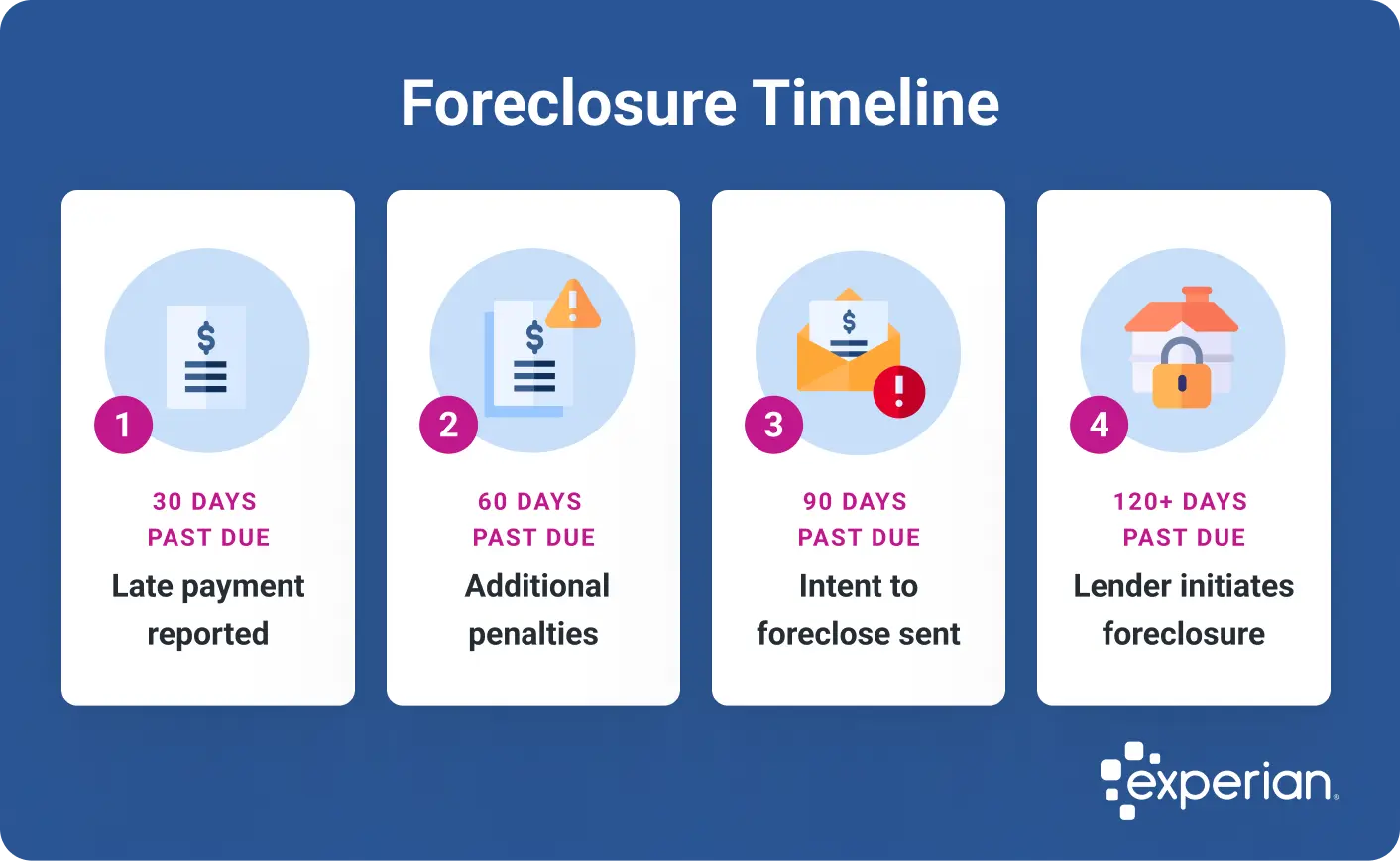

Foreclosure generally involves the following steps, in this order. Time intervals between steps can differ by jurisdiction and in accordance with lender policies.

First Missed Payment: 30 Days Past Due

Two to three weeks after the due date on your first missed mortgage payment, a letter from the lender will notify you that your payment is past due. It will also list measures the lender may take (up to and including foreclosure) if payments are not brought current promptly.

This marks the beginning of a phase known as pre-foreclosure. During this time, the lender will (and often legally must) attempt to contact you in an effort to get you to bring your payments current. If your mortgage is brought current within 30 days, you may be required to pay a late payment fee, but the late payment won't be reported to the credit bureaus.

Second Missed Payment: 60 Days Past Due

If you miss two mortgage payments in a row, you can expect additional letters along with phone calls, emails and/or text messages from the lender. Their contents may include notice that returning your loan to good standing will require paying late-payment penalties as well as the past-due payments.

Tip: Once 30 days has elapsed, the payment will be considered late and the late status will be furnished to the credit bureaus. Each subsequent 30-day period that elapses without payment will result in additional late payments being reported to the credit bureaus.

Third Missed Payment: 90 Days Past Due

After a third straight missed payment (that is, after you've defaulted, or gone 90 days past due on your mortgage), the lender may send you a formal statement of intent to foreclose after another 30 days. The lender may also publish your name on a list of debtors subject to foreclosure.

Learn more: How Long Does Foreclosure Take?

Foreclosure: 120 Days Past Due and Beyond

After 120 days without receiving a mortgage payment, the lender may initiate foreclosure. If a judicial foreclosure applies, a judge must be shown proof of loan default and authorize seizure and sale of the property, a process that can take several months and even up to one year. If nonjudicial foreclosure applies, the process can be completed in a matter of weeks.

How Does Foreclosure Impact Your Credit?

Foreclosure is a significant negative event in your credit history. It will remain on your credit reports for seven years, dated from the first missed payment that led to foreclosure.

The impact of a foreclosure on your credit scores lessens over time, and your FICO® ScoresΘ can begin to rebound as soon as two years after a foreclosure appears on your credit report; a full recovery could take years, however.

Tip: The foreclosure process can take anywhere from a little over a month to multiple years from the initiation of foreclosure, depending on where you live. The foreclosure may appear on your credit reports during that time or after the home is sold. But the first impacts of the missed payments leading up to a foreclosure come much sooner; creditors may notify the bureaus when a payment is 30 days or more past due.

Learn more: What Happens if I Default on a Loan?

How Much Does Foreclosure Hurt Your Credit?

The amount by which a foreclosure can lower your credit score depends on a variety of factors, including what your score was prior to the foreclosure. In general, individuals with higher scores tend to lose more points from their credit scores following major negative events.

You can track the impact of missed payments, foreclosure (and their diminished impact over time) by checking your FICO® Score and credit report for free with Experian each month.

Learn more: How Long Does a Foreclosure Stay on Your Credit Report?

How to Avoid Foreclosure

You have several options for avoiding foreclosure. The key is to contact your lender as soon as you anticipate struggling to make payments.

Here are some alternatives that can help you prevent the expense and stress of a foreclosure.

Loan Modification

If you can no longer afford your mortgage payments but have sufficient income to continue paying a smaller amount each month, your lender may agree to a mortgage modification—a permanent restructuring of your loan that reduces your payment amount.

Loan modification typically involves extending the loan repayment period and increasing the total amount of interest you'll pay on the loan, but it could be a way to remain in your home.

Learn more: How Can I Get a Mortgage Modification?

Short Sale

If you're upside down on your mortgage—that is, you owe more on the loan than the market value of the home—your lender may agree to a short sale. In this process, you sell the home at current market value and the lender accepts the proceeds as settlement on your loan.

There are significant downsides to a short sale. It doesn't provide you with any cash to put toward a new place to live. And, a short sale will cause your mortgage to be listed as not paid as agreed on your credit reports, which has negative consequences for credit scores. Also, any portion of your debt the lender forgives may be taxable as income.

Learn more: Short Sale vs. Foreclosure: What's the Difference?

Deed in Lieu of Foreclosure

In a deed in lieu of foreclosure procedure, you arrange with your lender to leave the home and hand over the title deed and the keys at an appointed time. Because this can spare the lender time and legal fees (in the case of a judicial foreclosure), some lenders may even be willing to provide a "cash for keys" stipend if you meet the move-out deadline and leave the home in good condition.

As with a short sale, your loan will be reported as not paid as agreed and any debt your lender forgives may be considered taxable income.

Learn more: How to Stop Foreclosure

How Does a Foreclosure Sale Work?

Once a home is foreclosed upon, it is typically listed for sale "as is" at a public auction. Many foreclosed properties are in distressed condition and bidders usually are not permitted to inspect them before the auction.

Foreclosures also may also have liens that must be paid by the buyer at the time of purchase. As a result, foreclosures often sell at auction for considerably less than their market value. This can create an opportunity for buyers willing to perform repairs and pay off liens (as the case may be), but it can be a risky proposition for inexperienced buyers.

If a foreclosure does not sell at auction, or when strict foreclosure transfers ownership directly to the lender, it is added to the lender's portfolio of what's known as real estate-owned (REO) property. REO properties, which may be available for purchase at less than market value, are not typically advertised or publicized but may be listed on a lender's website. In contrast to a public auction, where anyone can purchase a property on their own, buying REO property typically requires hiring a real estate agent or broker to handle the sale.

Learn more: Should I Buy a Foreclosed Home?

The Bottom Line

There's nothing much good about foreclosure for either the homeowner or the lender. It costs borrowers their homes and does significant harm to their credit. And it's expensive and time-consuming for lenders, who don't want to be in the business of selling real estate. If you're having difficulty making your mortgage payments (or if you anticipate difficulty doing so), it's wise to consult your lender as soon as possible to explore options for avoiding foreclosure.

If foreclosure nevertheless proves inevitable, your credit can recover eventually. You can track the credit impact of foreclosure (or its alternatives) and your eventual recovery with free credit monitoring from Experian, which alerts you to changes in your Experian credit report and your FICO® Score based on it.

Instantly raise your FICO® Score for free

Use Experian Boost® to get credit for the bills you already pay like utilities, mobile phone, video streaming services and now rent.

No credit card required

About the author

Jim Akin is freelance writer based in Connecticut. With experience as both a journalist and a marketing professional, his most recent focus has been in the area of consumer finance and credit scoring.

Read more from Jim